Martick's and Martick: 83 and Still Cooking

Morris Martick is 83 now. He was born here at 214 West Mulberry St. and has never lived or worked anywhere else. When Morris was a child, Martick's fronted as a grocery store that masked a speakeasy. Upon the repeal of prohibition in 1933, Morris's parents went legit and obtained a liquor license. When his siblings opted for their own careers, Morris continued with the one that's defined his life. Through the 50's and sixties, he was proprietor of Martick's as the legendary bohemian mecca that served the most heterogenous crowd any Baltimore watering hole has ever known. Martick's was the first bar in Baltimore to display art. It often featured the best Dixieland jazz outside of New Orleans. Interesting and diverse as the crowd was, Morris became fed up with some of the alcohol induced behavior that came with the territory. He closed in 1968, went to France, and returned in 1970 to open Baltimore's first French Restaurant. From the start the food was great. I know because I was one of the new French restaurant's first bartenders. If only he still had the tank from which customers could select live trout. When the pump failed, Morris never had it repaired because the critics never afforded it sufficient recognition.

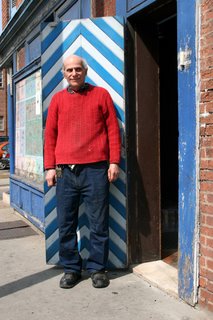

So much for history. It's 2006 now. Morris, lean and spry as ever, continues to work 15 hour days. He hasn't changed, nor has Martick's. You still ring a bell to be admitted. The bar, the tiles, and the woodwork have aged no less gracefully than Morris. Snakeskin still covers the west wall, aluminum the east wall, and the French bread lady statue remains.

Morris likes first to talk about food. His second favorite subject is what a small business Martick's is, the lack of of affordable help, especially anyone who "understands anything about food," and the bleak economic picture for such a business. Many former Martick's regulars dine out less as they get older. Others may not comprehend that Morris is still at it. Or they perceive the neighborhood as dicey. Advertising won't pay for itself, and if it did, it would bring in more customers than Morris could handle. Martick's is a treasure. There's nothing remotely like it in Baltimore or anywhere else. But for how much longer?

For the past 35 years, Morris has headed out every morning in his pick-up truck to purchase whatever ingredients his reservations book suggests are needed. "I have to go out and get all this stuff myself," he explains. "I'm so small that the suppliers would lose money if they let their drivers deliver it."

On a recent morning, I accompanied him. Beginning at 8:30, we went first to the F & S Maranto Bakery at 248 Pearl St. Inside were countless bins and trays, holding little more than an occasional loaf of bread. They had baked all night, and the trucks had already come and gone. Here and there, Morris finds five loaves. He takes them upstairs to the boss, Mr Maranto, with whom he likes to kibbutz. Mr. Maranto has been at F&S Maranto Bakery nearly half a century and is the great grandson and great nephew of its two founders. He believes that one of the loaves should be fresher and arranges for a replacement. No money changes hands. A larger check to cover numerous bread runs is easier for all concerned than dealing with it every day.

Next we head to Fells Point Wholesale Meats, which having outgrown its previous facility in Fells Point, is now located in southwest Baltimore. We pull up to the dock and walk up the steps. As at F & S Maranto, Morris is soon in an office with the CEO and all the top people. Morris orders and cuts a check for two pounds of veal cutlet, a 15 pound slab of beef from which to make beef burgundy, and a box of about a dozen duck breasts. That's more duck than called for right now, but eventually he'll use it.

Our final stop is a wholesale grocer on Old Annapolis Road, where Morris stocks up on cream, butter, canned tomatoes, a can of sweet potatoes for soup, 75 pounds of ice, and two bundles of paper towels. Only businesses are allowed to shop here. Morris presents his card and writes his check. Then it's back to 214 West Mulberry St.

We haul the booty upstairs. Morris goes immediately to work. He has two reservations for lunch and fifteen for dinner tonight. As he works, he quizzes me about cooking. "What's the one item that no kitchen can do without?" While I'm thinking, he answers: "Water." He's making a stock now. What are the three vegetables essential to a stock?" Again, he answers for me: "Onions, carrots, and celery." "What's the most basic kind of stock?" "Chicken", I answer,"or vegetable." "I'd give you an 'A' on that," says Morris. "When you're making a stock, what are you getting rid of?" he asks. "Water," I answer." He continues: "Your'e getting rid of water, you're dehydrating. Because why? Water has no flavor. You have to get rid of it. And the flavor comes from what? Whatever you put in, so basically, cooking is a matter of dehydration. It's a matter of removing water from the food." His waiter walks upstairs and passes through the kitchen. Morris begins cutting the beef we purchased this morning into cubes for the beef burgundy.

Before leaving, I ask Morris if he'll share with me one of his best recipes. He refrains. For an article I wrote ten years ago, he gave me his recipe for Lobster a la Martick, which I haven't seen recently on his menu. Nor did I ever try to prepare it myself. In contemplating whether to finally get around to doing so, I couldn't help but recall Morris's last words prior to my departure: "Cooking is an art. The cook is the artist. He determines what the color is, what texture, everything, by his cooking methods." Would a recipe alone be sufficient for me to duplicate the work of a cook as unique as Martick?